Where is ‘away?’

It must be somewhere, right?

After all, when we casually toss our waste, recycling, and compost into the bin, and say “I’m throwing this away,” we are referring to a final destination.

But where exactly is that?

As Annie Leonard famously said in The Story of Stuff, “There is no such thing as away.”

When we dispose of the waste we generate on a daily basis, it does not simply disappear. It has to go somewhere. But where exactly is that?

For most of us, the easy answer would be that waste goes to landfill, and recycling is repurposed into new material to be re-entered into the economy. Unfortunately, however, the process is not quite that simple. In an industry that is ever changing, the question of “Where does our waste and recycling actually go?” does not come with an easy answer.

Landfill

While all cities manage waste slightly differently, the vast majority of Canadian non-hazardous non-recyclable solid waste is sent to landfill. There are approximately 2,400 active landfills in Canada, which are wide ranging in size and operational capacities. However, it is important to remember that landfill space is not infinite. In order to maximize operational efficiencies, Vancouver sends excess waste to landfills in Washington and Oregon. In Ontario, excess waste is exported to landfills in Michigan.

However, even with these efficiencies in place, if we are looking at Ontario alone, there is only an estimated remaining landfill capacity of 122 million tonnes. This may sound like a lot, but given the large amount of waste that is generated in the province on a daily basis, the Ontario Waste Management Association estimates that this remaining capacity will be depleted by the year 2032. Notably, this estimate presumes continued export of waste to American landfills. Should the USA decide to prohibit Canadian waste imports, Ontario’s landfill capacity would be depleted even sooner – by 2028.

With that being said, there is a pressing need to find alternative methods to manage our waste in Canada. One such option, is incineration.

Incineration

Approximately 3% of garbage in Canada is incinerated, making it the least common method for waste disposal. Traditionally, those who have fought against incineration have been concerned about the environmental risks of incineration which include releases of pollutants into the area and potential health risks to surrounding communities. However, in modern facilities, advanced air pollution controls are used, which removes 99% of the dioxins and furans emitted from incineration, drastically reducing these risks. Many incineration facilities focus on Waste to Energy (WTE) technologies, that also provide a unique opportunity for waste to be utilized as a resource.

While incineration may be underutilized in Canada, it is growing in popularity in other parts of the world. In countries including Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland, approximately one-third of the waste is incinerated. In Japan, this number leaps to just over 70%.

However, in Canada, a lack of existing facilities and investment in the technology limits the availability of this opportunity, resulting in 97% of the non-divertible waste that we generate, ending up in landfill.

But what about the waste that can be diverted? Material that can be diverted away from landfill or incineration programs would be the organics (food waste) and recyclable materials that are source separated. These materials must be handled very differently than waste.

Organics

One of the best opportunities for us to reduce our environmental impact is to participate in an organics program, diverting food-waste away from landfill. Organics can be alternatively managed through a compost program. Currently, there are an estimated 313 compost and anaerobic digestion facilities in Canada, offering municipalities and businesses the opportunity to divert their food waste away from landfill.

However, many municipalities across the country continue to lack the infrastructure to provide food-waste programs to their residents. Whether that be a lack of collection and transportation services, local facilities, or an issue with funding, there is a significant opportunity to further increase waste diversion across Canada, through a stronger focus on compliance in existing organics programs, and development of new ones.

Organics and food waste is not the only opportunity to divert material away from landfill through composting or other methods. In fact, when it comes to waste diversion, the first thing that comes to mind is often the most popular approach – recycling.

Recycling

‘Reduce, Reuse, Recycle’ is a phrase that everyone knows all too well. And for many of us, there is a sense of accomplishment that comes when we partake in these famous ‘3 Rs.’ However, when we toss our recyclable material in the blue bin, most of us do not actually think about what happens next. In fact, for the vast majority of the general population, how recycling actually works is a mystery – and a complex one at that.

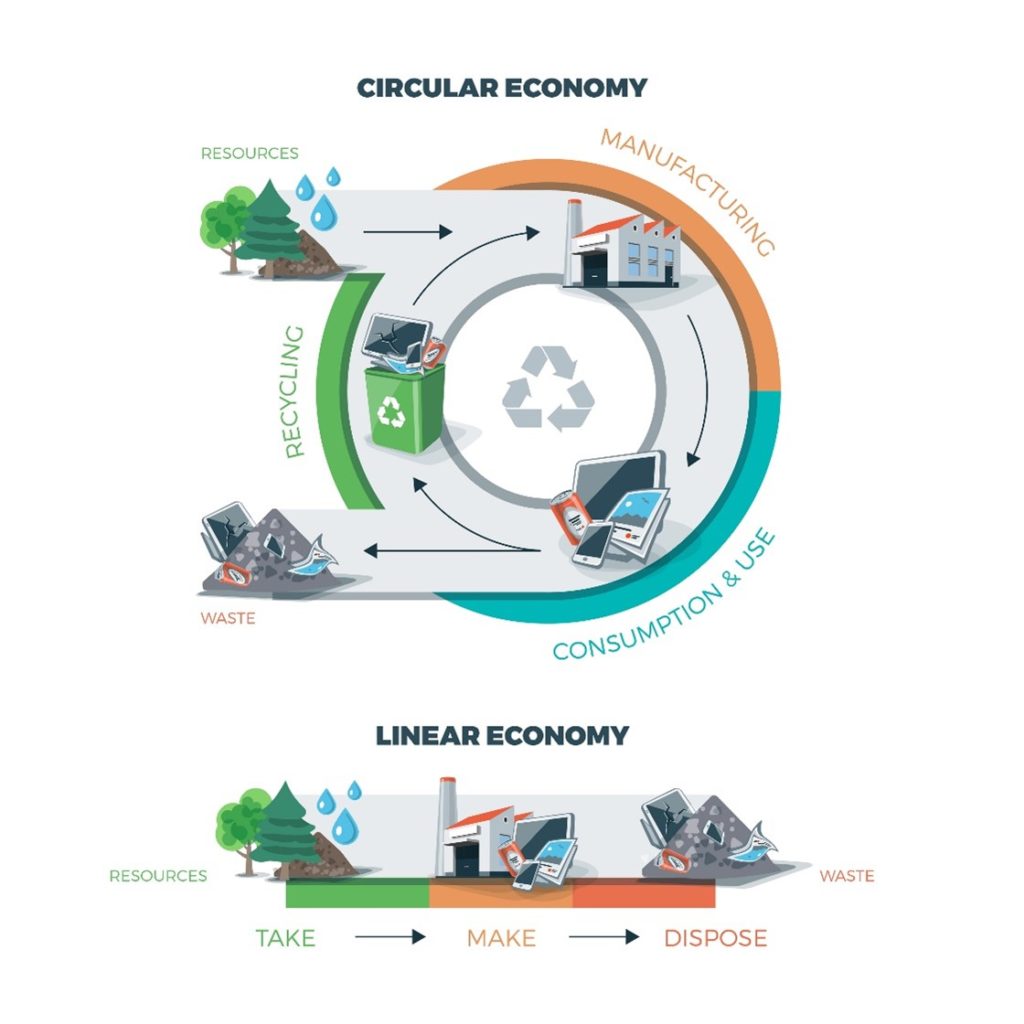

In an ideal world, the process of recycling would follow a simple and straightforward pattern. First, recyclable items would be placed in the bin by consumers. Next, the waste contractor would collect the material from those bins and bring it to the local MRF (Material Recovery Facility). At this facility, the material would be sorted and categorized by material type (ex: plastic, aluminum, paper etc.). This material would be baled, and then those bales would be shipped and sold to the recyclers who would then repurpose that material, thus re-entering it into a circular economy.

Unfortunately, in an ever-changing industry, it is not that simple. Due to several ongoing factors, there are challenges that the recycling industry has faced in the past several years that have made what at surface seems like a straightforward process, more complex than ever before.

China’s Ban on Imported Recycling

In 2017, China announced the ‘National Sword Policy,’ a policy that banned the important of certain types of solid waste, including materials that were considered ‘recyclable.’ Often referred to simply as the ‘National Sword’ or ‘Green Sword,’ this policy irrevocably changed the landscape of recycling.

Up until 2017, China was the world’s biggest importer of recycling. However, this policy drastically minimized the largest market for MRFs here in Canada, the USA, and other countries, to ship their recycling to. The reality is, many of the recyclable materials were sending to China, were not actually recyclable at all. Highly contaminated or low-quality materials were ending up in landfill, in storage facilities, or worse, polluting green spaces and waterways as mountains of litter began piling up.

The National Sword Policy was aimed at preventing China from becoming the dumping ground for other countries, who were looking for a home for their waste and recycling. The practice of importing international waste had become increasingly unsustainable, leaving China with an influx of material that other countries had labelled as ‘recyclable’ that had no true end market.

As in any industry, if the largest customer for your product disappears, its value diminishes. That is exactly what has unfolded with recycling in the years since 2017. As China halted their import of recycling, MRFs found themselves with bales of ‘recyclable’ material with no end market to sell it to. This crisis pinpointed a major flaw in the pre-existing recycling system. We, as consumers, were simply creating too much waste, for the system to be sustainable.

Increasing Contamination Rates

Contamination is one of the most pressing issues facing the recycling industry here in Canada, and one that we as consumers have the power to change. Contamination refers to when non-recyclable material is placed in the recycling bin, thus contaminating the material that could have otherwise been diverted away from landfill.

There are two key causes of contamination that we see on a regular basis. The first cause is what has colloquially referred to as ‘Wish-Cycling.” Many people put non-recyclable material in their recycling bin, in a wishful attempt to have it diverted away from landfill. While they may think they are doing the right thing, they are in fact contributing to a major problem that recyclers are trying to navigate. The main root of this issue is a lack of education on recycling programs. Many people honestly believe the material they are placing in their blue bin belongs there, even though it is not technically accepted.

The second cause is unclean recycling. We see this when residual food waste is left behind in a container (think pasta sauce left in the bottom of a jar, or grease waxed paper from the bottom of a take-out container).

The issue with contamination is the inevitable cost. When contamination exceeds an acceptable limit, MRFs are unable to accept it, which means waste haulers have no choice but to send it to landfill, essentially paying to manage the garbage twice – first to collect it as recycling, and then second to send it to landfill as waste. Most often, this cost is passed back to the customer, meaning an increased operational cost.

The other cost that must be considered is the environmental cost of sending material to landfill that could have been otherwise diverted. As limited landfill space runs out, it is more important than ever to conserve it, and only send material to landfill that truly belongs there.

The Plastic Crisis

The plastic crisis is undoubtedly one of the key issues that the recycling industry is facing today. With at least 14 million tonnes of plastic ending up in our oceans every year, it is clear that there is a pressing need to reduce the amount of plastic we use, while learning to manage the plastic we can’t avoid more responsibly.

At surface level, it may seem easy to brush off the plastic crisis as a different problem than the ones facing the recycling industry. After all, plastic that is managed through the recycling industry should not end up polluting our green spaces and waterways. But the unfortunate reality is that it is. Used plastics simply do not have significant value, and the end market is limited for it, thus resulting in significant amounts of this material ending up in landfill or contributing to ongoing pollution. Therefore, the solution to the plastic crisis lies not just with us as individual consumers, government legislation, and corporate responsibility – but on the recycling industry as a whole.

The Solution

When reviewing the issues facing the recycling industry today, it would be all to easy to declare the situation hopeless. But the truth is, these challenges simply pose the opportunity for innovation and change, to make recycling more sustainable and effective overall.

When tackling the effects of the National Sword Policy, MRFs have sought out alternative markets to China to ship our recycling to. However, to prevent history from repeating itself, we must look at what got us here in the first place.

Recycling contamination rates and the plastic crisis are two of the most significant factors that provide us with the opportunity to make a change. To reduce recycling contamination, we must educate ourselves on what materials are actually accepted in our recycling programs.

Many people believe all plastics and all paper products can be recycled, however that is simply not the case. Take the time to learn what materials can actually go into your specific program, recognizing that there are differences from region to region, and from service provider to service provider.

Perhaps even more importantly, we must work to reduce the amount of plastic we are generating in the first place. Not only will this ease the burden on the recycling industry and mitigate our impact on the plastic crisis, but it will also reduce the amount of material we send to landfill.

Why It Matters

Knowing where our waste, organics, and recycling goes empowers us to make responsible decisions when it comes to tossing our material in the bin. By educating ourselves on the true story of waste and recycling, we can enact change around us, most importantly in our own daily habits.

We can never forget that ‘There is no such thing as away,’ and when we throw things away, they do have an end destination. Becoming aware of this is the first step towards change and sustainable responsibility.

Learn More:

Where Canada Sends its Garbage – 10,000 Changes

Canada’s dirty secret – Canadian Geographic

Solid waste diversion and disposal – Government of Canada

Municipal solid waste management in Canada – Government of Canada

Best solution for plastic waste is incineration – MacDonald Laurier

China Doesn’t Want the World’s Trash Anymore. Including ‘Recyclable’ Goods. – Forbes

What is the National Sword? – Centre for Eco Technology

Many Canadians are recycling wrong, and it’s costing us millions – CBC